Right to Repair: 6 ways to make a product that lasts

Last week, new Right to Repair rules came into effect in the UK.

This means manufacturers will now have to make spare parts available for certain electrical products within 2 years of product launch and for a minimum of 7 or 10 years, depending on the part. Some of these spare parts will be available directly to consumers while some will only be available to professionals if the repair job is difficult or unsafe.

It’s a step in the right direction. Empowering customers to extend the lifespan of their products is crucial if we are to break away from our take-make-waste economy and begin to tackle the enormous issue of electronic waste.

For now, the Right to Repair rules are limited to a relatively small number of appliances including washing machines, washer-dryers, dishwashers, refrigerators and TVs. Laptops, tablets and smartphones, along with many other household appliances, are still exempt.

But the change is coming. Customers will soon demand their right to repair all kinds of products, and brands that are ahead of the curve in enabling repair will win favour.

The role of design in repairability

Providing spare parts is just a piece of the problem. Repairing a broken product needs to be easier, more affordable, and more desirable than simply buying a new one.

That’s where designers come in.

A product’s repairability is determined at the design phase. Design decisions from material selection to how the product is assembled will all impact how likely a product is to be repaired rather than replaced.

Here are 5 ways to make a product more repairable through design.

1. Design for emotion

Perhaps the best way to ensure a product gets repaired is to make a product that people actually want to keep in their lives. Building sentimental value is a challenge in today’s throwaway society, but people are much more likely to try to fix something that is important to them. Your customers need to value your product enough to decide it’s worth repairing rather than replacing. A user-centred design process that uncovers user’s needs and desires is vital for designing solutions that add genuine value to people’s lives.

(Image: Anglepoise Type 75, the kind of product that people will keep for generations)

2. Design for disassembly

Designing a product that comes apart easily will improve the chances of it being repaired. Make sure that any broken component can be identified, removed and replaced without special tools (better yet, no tools!) and without damage to other components. Use removable fasteners over adhesives, standard screws over security screws, and design snap fits to be separable. The design of the product itself should make clear how it comes apart. Parts that are most likely to fail should be the most accessible to remove.

(Image: AIAIAI TMA-2 modular headphones that are designed with disassembly and repair in mind)

3. Design for modularity

For products where complexity prevents each part from being individually replaceable such as in consumer electronics, consider a modular design. Being able to easily remove modules or sub-assemblies allows broken components to be replaced with minimal waste of working parts. This approach can also help end users make repairs themselves when replacing the individual component might ordinarily be difficult or unsafe and require a professional service.

(Image: Fairphone’s modular smartphone that enables users to replace or upgrade individual components)

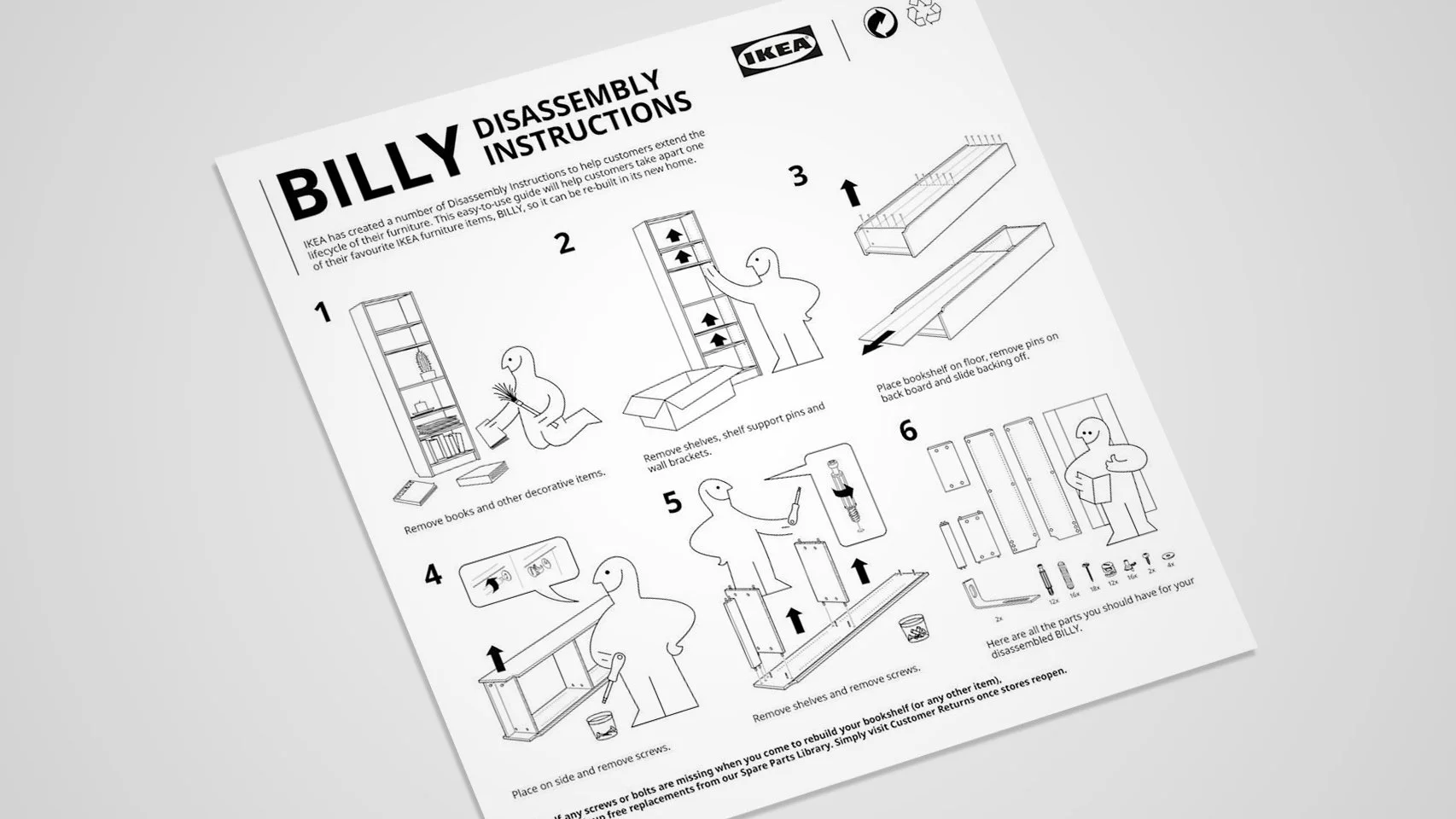

4. Design a repair guide

As champions of the user, designers can use their voice in the development team to make sure effective repair documentation is provided. Making these instructions accessible to all and easy to understand is paramount to educating users on repair. Communication of potentially complex repair processes should be treated as a design challenge in itself to make the repair guide as user-friendly as possible. While AR technology is unlocking new ways to communicate and carry out repairs with digital graphics overlaid on the physical product, even a set of simple diagrams will help extend product lifespan.

(Image: IKEA disassembly instructions, a great example of clear communication)

5. Design a repair service

If repairing your product takes specialist skills or equipment, consider supporting your customers with a repair service. Go beyond making spare parts available and take responsibility for your products beyond the point of purchase. Not only will you make sure your products stay in action and out of landfill for longer, a repair service will earn you customer trust and loyalty. Explore how a repair service might work for your products and make it easy for your customers to take you up on the offer.

(Image: Patagonia’s repair facility that refurbishes used clothing for re-use)

6. Design for durability

Prevention is better than cure, after all. Careful consideration for the durability of the product at the design phase can minimise the chance of something going wrong in the first place. Your choice of materials will inform the robustness of the product – preventing breakages and cosmetic damage that might need repairing. Reduce the complexity of the design so there are fewer parts that might fail. Make it easy for users to maintain the product in good working order to avoid greater damage being done and extend its lifespan.

(Image: Dualit NewGen Classic toaster, a product designed to last a lifetime in a sector with an average lifespan of 6-8 years)

Every time we create a product we always keep in mind that we’re actually designing the thousands of units that will be made, bought, used and disposed of.

Each repair is one less product in the waste stream and another replacement purchase avoided. That’s a huge impact to be made if we consider repairability early enough in the development process.

If you’d like to explore repairability as a method for not only reducing the environmental impact of your product, but winning and retaining loyal customers — get in touch and let's have a chat. We’d love to help!